Videogames form an exciting part of the modern day cultural landscape.

Whether created for leisure, or more serious in their intent, videogames are being utilised in more branches of society than anyone could have predicted.

They are helping to shape our broader understanding of the dynamic between people and place.

For those curating the public realm, there is a necessity to broaden our horizons, understanding that places are not just designed, constructed and managed, but that they are also programmed.

The parallels between virtual, hybrid and physical environments has become too close to ignore, raising the question, can we and should we make video games a more integral part of the public realm experience?

Landscape Architects play a pivotal role in the curation of outdoor spaces. We inherently understand how those spaces will function, as a balance of man-made and natural processes, to achieve sustainable design resolutions.

We also have an expanding role in how those spaces are planned and programmed through urban design and place making. Our understanding of how people use space must diversify to acknowledge and incorporate this new digital layer of information that we interact with.

The games industry has become a powerful medium of entertainment that has connected people globally and socially. It is an industry that has transcended age brackets and cultural boundaries, that has allowed people to reinvent themselves, and spend as much time gaming as a part time job – out of choice.

Whilst videogames are undeniably a sustained form of entertainment, they have drawn criticism on issues such as censorship, addiction and obesity. The default view on videogames by many seems to be that the time spent on games takes away from the time that could be spent outdoors.

‘Videogames…are often accused of ripping people out of the natural world and placing them into an artificial one.’ – ‘How to do things with videogames’, Ian Bogost (2011)

Landscape architecture may seem unorthodox in advocating for the games industry, but it through the evolving portrayal and use of the landscape, and play value it offers, which draws parallels.

It raises the question – should people be playing videogames less or does outdoor play need to be as accessible and engaging as digital play?

At a lecture in Adelaide in 2014 author and Journalist Richard Louv spoke about the emergence of the global ‘nature play’ movement, sighting a ‘growing unease with technology’.

This movement emerged because our concept of the landscape has changed over the past few generations. Children venture outside less and reside closer to home when they do, restricting their ability to build up an accurate picture of what the landscape is and what it has to offer.

This is due to a wide range of issues, not confined to parental fear over safety and security, and accessibility of quality open space. Culturally, play is being impacted by a risk averse, blame driven society.

Meanwhile, our use of technology and screen addiction is now being portrayed as a threat to society, including our exposure to the natural environment and therefore nature play. Can these modes of play can coexist? There are common goals where getting people outdoors and active is concerned, including entertainment and exploration.

The experience of landscapes in video games might serve a greater purpose than simply a setting for a game.

‘The experience of playing (Golvellius 1987) was a journey of discovery; discovering new lands and discovering ways of crossing previously encountered natural environments. It wasn’t just a game but an experience, and in many ways no different to one that children play out continuous time in parks and back gardens, exploring the environment in the hopes of finding something new and exciting albeit in the confines of a virtual space.’ – ‘Virtual Landscapes’, Umran Ali (2012)

Digital gaming itself has undergone a rapid evolution over the past 40+ years that has seen the widespread domestication of digital gaming devices.

A Guardian article highlighted:

‘for a time video-gaming offered a level of physical and social interaction, at the arcade or through multi-player sofa games that friends and family members could play at the same time, in the same room. Then multi-player videogames moved online, and fellow players became physically removed from one another, if not completely anonymous’ – The rise and rise of tabletop gaming, The Guardian 2016

To the surprise of many, it hasn’t been any domesticated game systems that has proven to be the most flexible in introducing games to the masses – it has been the humble mobile phone.

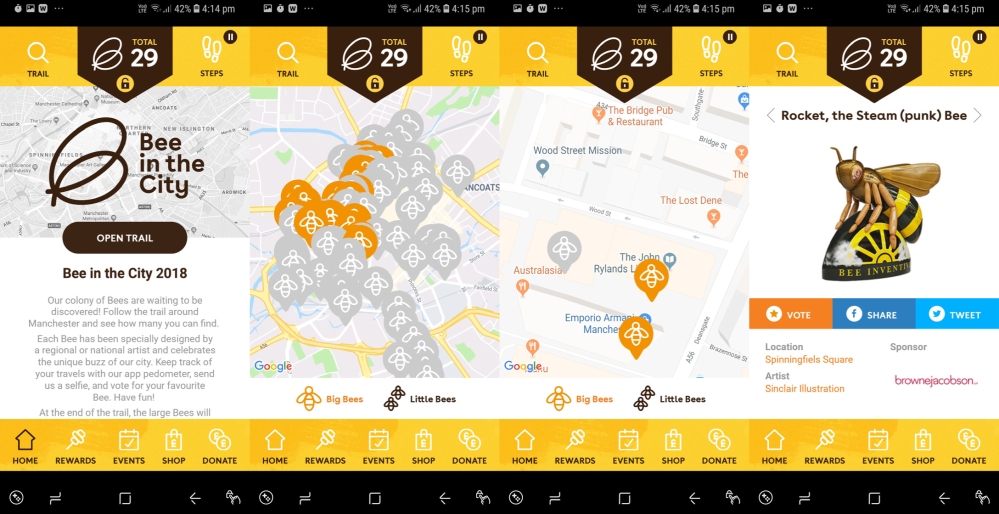

Although location based mobile games have been around for some time now, it is the emergence of Pokémon Go that has caught the imagination of the public. The number of people playing has forced everyone to take notice, but what seems to have been reported prolifically is where the game has gone wrong, rather than the many ways it has gone right.

What it has done is force new questions on how it can be successfully integrated, which I believe can help advance our understanding of how games can enhance the experience of the public realm and educate people over the benefits.

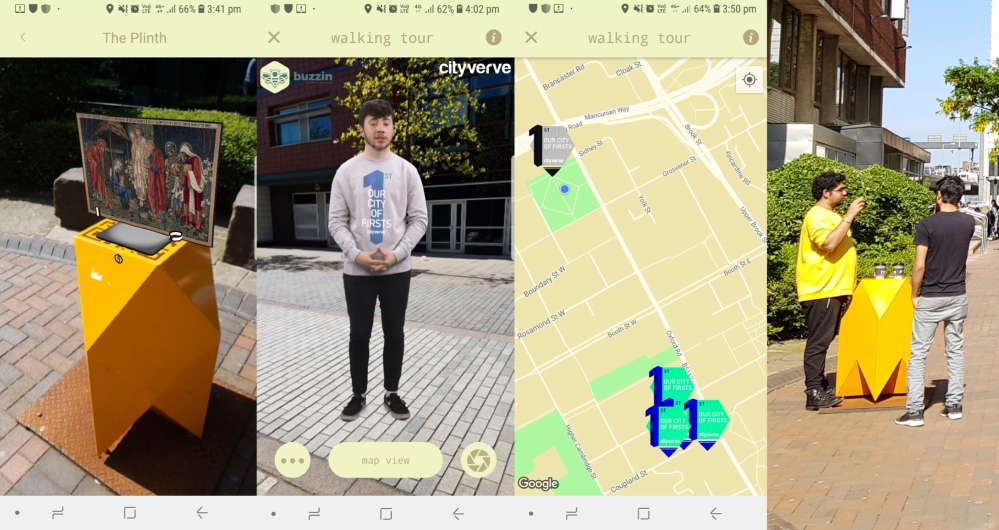

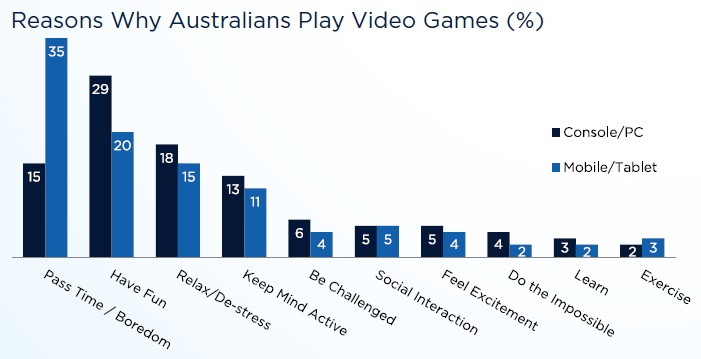

The Digital Australia report provides valuable statistics in relation to the videogame industry. The diversity of people playing games and the frequency they play them highlights the cultural significance of the industry.

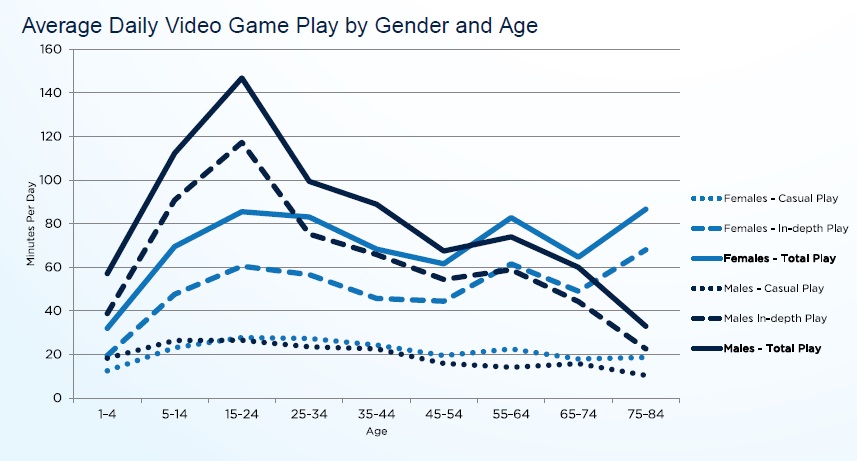

When we talk about play in the public realm by default we might think of playgrounds and a specific demographic. In the context of video games all age groups play games and they account for 68% of the population (around 16.5 million people). The average age of players is 33. People who grew up playing games continue to play them. This forces us to think more broadly around the notion of play.

So why are we playing games? Amongst the most prominent reasons cited in the Digital Australia report, were to have fun, keep our minds active and relieve boredom.

It was, however, the less cited reasons that caught my attention.

We are less likely to play games to learn, to exercise, or to socially interact. These are all commendable attributes of playing games, but I think that gamers are not oblivious when they are pushed onto them too heavily. It’s a balancing act, but one that cannot be ignored with the couch-potato traits often associated with games.

The Heart Foundation noted:

‘There are both long-term and short-term impacts of prolonged sitting. These include an increased risk of becoming overweight or obese, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and premature mortality, an increased number of musculoskeletal conditions and eye strain’.

Encouragingly they also noted:

‘If games like Pokémon Go get people active, and improve their heart health as a result, we say go for it. We all need to minimise prolonged sitting by breaking it up with periods of activity’.

As adults we have a recommended weekly level of moderate to intense physical exercise:

150 to 300 minutes of moderately intense physical activity

or

75 to 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity

http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines

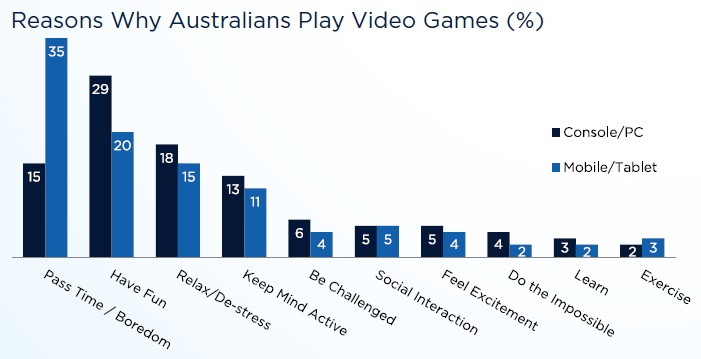

If we take those figures and compare them to the average time spent playing videogames – a reported 88 minutes a day, there is a clear opportunity where outdoor gaming can have a healthy impact.

It is surely only a matter of time before studies occur to determine the extent of health benefits associated with Pokémon Go and it won’t be the first time a study of this nature has occurred.

Active behavior encouraged by the Nintendo Wii created much interest on the domestic front with games like Wii Sports. Whilst a study confirmed that Wii Sports didn’t burn as many calories as actual physical activity, this is really where mobile games have stolen a march on their domesticated forbearers.

For example the mobile game ‘Zombie run’ encouraged players to sprint at intervals in the outdoors to escape hordes of zombies. It was unique in that it didn’t rely on screen to time for players to participate. Many of those games lost momentum because rewarding players with monotonous in-game achievements (e.g. distance markers) became meaningless once those milestones were achieved. Games have to do more, they have to be meaningful in other ways.

So where else have videogames and landscape converged?

A significant part of play is the narrative we assign to it and I think this is an essential ingredient in videogames, physical play and the broader landscape.

‘Play is the fiction of doing’ – Oscar Barda, ‘How I found a definition for games after searching for 16 years’, Gamasutra blog 2016

Story City, a choose-your-own adventure story app, connects people with place via fictional stories. The app empowers the reader to make choices on where they would like to explore, linked by decisions made in a fictional narrative and guided by GPS.

Further to current location based games, the strength of Story City lies in its ability to capitalize on the work of local writers, musicians and artists.

Each story is unique and actively links in with the context of real locations.

For the Port Adelaide edition of Story City, we have been working with a local primary school, testing stories, generating art and creating music to include on the app, providing an authentic experience that will resonate with locals and inspire visitors to explore the area.

Whilst many location based games are made for a mass market, Story City demonstrates the flexibility to adapt game content and empower the local population.

There are other games emerging offering a closer relationship with the landscape by making their input an integral part of the game.

The Questagame app encourages players to scan flora and fauna outdoors, which they are rewarded for in the game. This reward varies at a rate depending on the rarity of the species. This mechanic is an excellent example of how games can build up a database of useful information and has already been endorsed by multiple agencies, academic institutions and botanical groups.

Interestingly, a similar scanning process was also an integral part of the recent game No Man’s Sky, which embedded the flora and fauna on procedurally generated planets for gamers to explore, who were also rewarded as part of these discoveries.

No Mans Sky (2016)

Unfortunately, our public realm doesn’t often embrace the opportunity for play and games.

Playspaces are the broadly accepted location for ‘play’ to occur.

There is a saying, ‘Nature doesn’t stop at the boundaries we draw for it’, and perhaps, neither does play.

Some of the biggest strides in games in the public realm has come via play equipment design. Equipment has been adapted to incorporate button operated, light and sound based games. The games require a combination of movement, balance and speed and was pioneering in many respects. This fusion of digital and physical components has been described as ‘Playware’ (‘Playtesting the digital playground’, Gunver Majgaard, Carsten Jessen, 2009), and might just be to playspaces what Pong was to the domesticated games industry.

Kompan’s ‘Icon’ range

These integrated ‘Playware’ games don’t rely on a screen, allowing the conventional physical benefits of playspaces to flow naturally whilst engaging children in a hybrid play experience.

There have been other playspaces that have incorporated brands as part of their theme, in addition to mobile apps themselves. Rovio Entertainment and Lappset (who are represented by Active Recreation Solutions in Australia) combined to develop a series of Angry Birds playspaces.

The entrance to Angry Birds Land, an Angry Birds-themed activity center within the Sarkanniemi Park, is seen near Tampere, Finland, on Friday, May 4, 2012. Rovio Entertainment reported FY sales of EU75.4m. Photographer: Juho Kuva/Bloomberg

The ”Angry Birds” mobile phone game, designed by Rovio Mobile Oy is displayed, on a white Apple Inc. iPhone 4 at a mobile phone store in London, U.K., on Thursday, April 28, 2011. Apple Inc. may face greater scrutiny in the European Union than the U.S. as regulators investigate possible data-privacy lapses betraying the location of iPhone and iPad users. Photographer: Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg

The association with popular culture helped to raise the profile of the playspaces in a similar way to the use of the Pokémon brand by Niantic.

There are some peculiar measures emerging elsewhere in the public realm to address mobile gamers. The introduction of ‘smart paving’ and similar measures to guide the neglectful mobile user, removes individual accountability and takes away the liberty of self-assessment and freedom of movement. This harks back to the brutalist urban design approach of the 60s, creating walking deterrents to ‘guide people’.

That said, there is a common language on how we understand people function in spaces, whether considering open world virtual environments or real world environments, and increasingly where location based games, and integration of augmented reality is being developed.

Landscape Architects from Fletcher Studio in San Francisco worked on a videogame called the Witness. It was an Island based, first person, puzzle game. Like numerous open world game environments, the non-linear gameplay and pace of the game allowed greater opportunity to observe and explore the Island. The landscape was iconic, mimicking different environments and taking influence from different periods of civilization.

The Witness (2016)

Lead Landscape Architect Deanna Van Buren highlighted that

‘Given the increasing number of people who “see” the built environment digitally, designing environments for the electronic gaming industry can have an impact on the public’s appreciation of good design and on their demand for better quality in their physical world’.

Lead game developer Jonathan Blow said that the guidance and advice of the architects helped to craft the island in a way that felt more immersive for the player because all the details were in place.

The Witness sets a precedent for potential collaboration between landscape architects and game designers.

But why do people play games of this nature?

Speaking of his earlier years spent in built up UK suburbia, Dr Umran Ali, expressed some other sentiments. He noted:

‘Video landscapes offered me the possibility to play, albeit in a virtual space, and experience the natural spaces I craved for’ – ‘Virtual Landscapes’, Umran Ali (2012)

He was right, we do have an innate desire to experience and be in the landscape, but to what extent does this satisfy our needs if delivered artificially?

It is a confronting concept to think that the virtual landscapes might provide a significant part of our exposure and opportunities to explore the landscape. It could be argued that some of the most recognizable landscapes don’t physically exist – they are virtually embedded.

The visuals and audio of games have become so realistic, with compelling narratives and vast game worlds, it is little wonder that Australians are spending so much time playing.

Ali also noted:

‘For many players experiencing changes in the landscape rather than pursuing the goals of the game… (is) more appealing than the narrative or the primary quest of the game’ – ‘Virtual Landscapes’, Umran Ali (2012)

Not all games possess these qualities or intend to. For every Firewatch there is a Flappy Bird, but there are different types of games for different types of gamers.

Firewatch (2016)

Flappy Bird (2013)

There is a term to describe these artificial landscapes (The Witness’s and Firewatch’s of the world), these surrogate landscapes that we roam in the confines of our screens. The idea of a ‘surroscape’, in shaping our interpretation of the physical landscape may seem perverse at first, but consider this:

Not everyone has means of accessing rich, stimulating environments, whether it be down to location, weather, physical and psychological limitations, financial restraints or simply a lack of knowledge that these environments exist.

Urban densification, over-population, and climate change are huge global challenges that are impacting on our experience of the landscape. We could yet rely on virtual landscapes in ways beyond play and games that supplement our livelihood.

Aliens (1986)

It becomes a question of – what is the human need for exposure to the landscape?

In Summary

- Videogames add value the experience of the landscape

- They encourage more active behavior without being the primary focus

- They offer a sustainable, adaptable opportunity for place activation

- And they allow a unique sense of place to develops

This article was adapted from the presentation ‘Play and Landscape in the Age of the Artificial’ at the Open State: Future Cities event in Adelaide 26/10/16 and can be viewed online https://youtu.be/45AII4lvIT0?t=8m20s